Standing Where They Stood: The Emotional Pull of Ancestral Places

And the uncanny incident of the lost key

Why is it so meaningful to return to your roots? To where your ancestors are from? To visit places you only know from stories and pictures?

I’ve asked myself that every time I traveled to my grandparents’ hometown, Liberec, in the Czech Republic. Standing in front of the villa my grandparents used to own feels like I’m visiting an old friend; sitting in the ornate Viennese-style café they used to frequent makes my heart soar.

In Liberec, I am not only able to see and touch the past, I can be inside of it.

Nevertheless, why would I feel such emotion and travel back again and again, to a place I myself never lived in? A place whose memory I only inherited?

Before my memoir Jumping Over Shadows came out, my sister and I traveled to Liberec; I flew from Chicago, she drove from Munich, Germany. Since a good part of that book takes place in Liberec, recounting the rather dramatic family history there, we wanted to take pictures of various locations there (and me at them) that were featured in the book, for promotional materials. The header image on my home page of me wearing a pink skirt, sitting in front of the museum around the corner from where our grandparents used to live, is from that trip.

After we had wrapped up our photo shoot, we decided to drive out to the village of Hamr na Jezeře (the erstwhile Hammer am See), where our grandmother, whom we always called Oma, had spent childhood summers at her grandparents’ mill.

Will the building still be there?

Whenever I set out to visit these sites of the family’s past, I worry that they might not be there anymore. I am emotionally attached to these places, but I have no control over them.

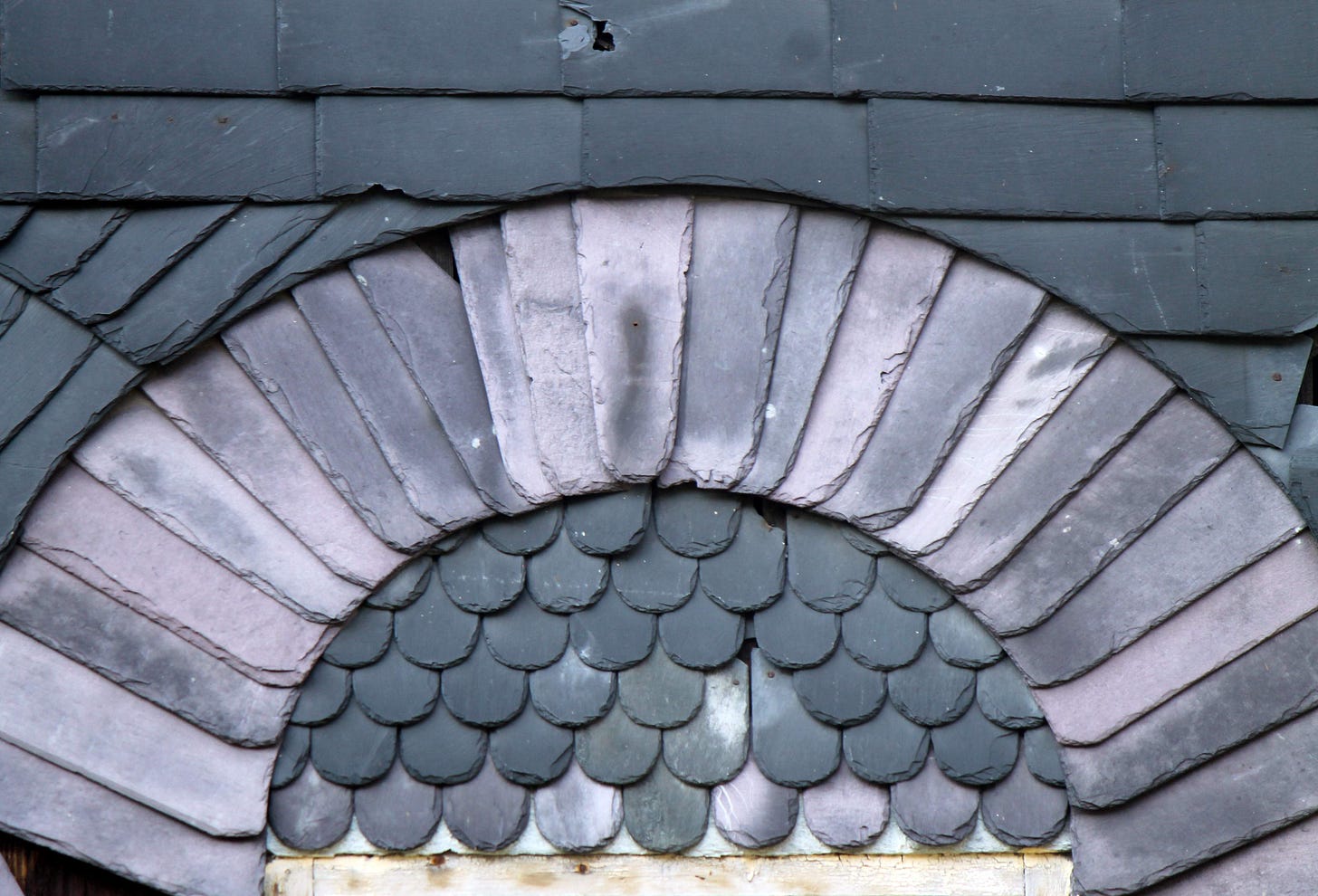

Thankfully, the mill was still there: an abandoned ruin in blue-gray shingles tucked into the bend of a country road. Presumably it has stood empty since after World War II, when our family, along with everyone else of German heritage, was expelled from Czechoslovakia.

This was not the first time I visited the mill; I had been there with my brother in 2002. Back then, there was still glass in the windows on the upper floors.

Taking Home a Piece of the Past

Already on my first visit, I fell in love with the intricate patterns of the slate shingles that covered the outside walls of the upper floors. Now many were dangling. My sister and I even found two shingles on the ground, entirely intact. We each took one along “to do something with.” Mine, shaped like a gothic window, now resides one of my bookshelves in Chicago.

On the mill’s covered walkway, shards of glass and siding crunched under our feet.

I could just see our great-great-grandfather standing at the walkway’s railing, surveying the courtyard where now trees grew in the mud that had washed down from the road that swings by the mill.

According to Oma, her grandfather always wore a carnation in his lapel, an oddly dapper outfit for the owner of a saw and flour mill, but—“he loved flowers.”

Oma’s grandmother was more practical: looking at a potato plant, she could tell whether its bulbs in the ground were ripe or not. She was generally exasperated with Oma, who “had only books in her head” and loved to sit in one of the mill’s windows, munching butter sandwiches as she read.

In the corner of the walkway, the mill’s main entrance door creaked open when my sister pushed it. We poked around the inside. The rooms stood silent and empty, draped in cobwebs, sunlight streaming through the broken windows.

It was so moving to walk through the same rooms Oma had played in, to be inside the very walls that contained her childhood stories. To imagine all that family life buzzing about!

Buildings and places last longer than we do. This decrepit mill, this very spot on Earth, contained our history, and allowed us, for a few moments, to touch the past.

We didn’t trust the integrity of the stairs to visit the “big room” we knew to be upstairs, where Oma used to sleep, unperturbed by the mill’s erstwhile noises: the gong of the grandfather clock, the rush of the mill stream, the churn of the mill’s wheel.

Outside again, we thought it would be fun to figure out where the actual mill operation had been. Searching for the mill stone, we stumbled through the thickets around the building until we found ourselves teetering on the rim of what seemed to be a concrete grid, overgrown with grass and weeds. A jungle of shrubbery beckoned below its rim.

As we discussed whether we were really standing on the former mill contraption, my sister reached into her pant pocket for a tissue. With it, her car key slipped out and dropped into the porous ground below us.

We stared at each other.

“This didn’t just happen,” I said.

She groped among the weeds and peered into a few of the grid’s holes.

“It’s gone. I can’t see a thing.”

Trying to keep calm, I said, “We can’t get it from here; let’s go around.”

We made our way to the walkout basement where a door stood open. However, our cell phones’ flashlights didn’t stand a chance against the pitch black inside.

“Let’s try from below,” I reasoned, meaning the jungle we’d looked down upon when the key fell. “There should be an opening if the mill stream came through there to operate the wheel.”

Now we really had to figure out where the mill stone had been! The stream that must have provided the energy for the mill was nowhere to be seen nor heard. It had probably been rerouted to the now defunct Communist-era uranium plant across the road.

We ducked through the shrubbery until we reached the wall we had previously stood upon, where indeed a hole gaped at us.

My sister stuck her head in.

“I see the key! But I can’t reach it!”

She fished with a twig until the key dangled in front of her face.

“How extraordinary,” she said, as we exhaled. “That this should happen here, in Oma’s place!”

As we made our way back through the thickets and snapped a few more pictures of the mill’s overgrown glory, we kept marveling at the fact that we had lost the key among the remnants of our family’s past.

Driving away, it felt as if our anxiety over the key’s recovery had left a bit of our hearts at the mill.

Perhaps returning to our roots by visiting the places of our family’s life before us fills a hole in our understanding of the past, particularly when the attachment to a home was broken by world events.

Our family’s mill was the manifestation of a hole in our family history, a property that had to be abandoned involuntarily. How symbolic then, that our car key should drop into a literal hole at that very site, and that it dropped into the very hole where the mill’s turbine used to churn to generate the family’s livelihood.

I felt as if that key, flying by the layers of concrete, earth, and roots as it fell from our sunny world to the dank cavern below, stitched together decades of family history.

To boot, the incident of the lost key gifted us with our own story to tell about the mill. Now we lived there a little, too.

I really enjoy your writings. Especially this one. As I get older, I long to go back in just look at my grandparents houses in Wisconsin. Brings back such floods of memories.

Wonderful trip and story! Aren't you glad the key dropped .... I am too old to travel anymore but really enjoy other's trips and explorations into our family history.