Translating Myself and Finally Finding my Voice as a Writer

Massaging an AI-generated translation to sound like me

I grew up bilingually, and thus there are two language tracks in my brain: one for English, one for German.

There’s also the foreign language compartment: Until a few years ago it was dominated by French, with one seat meekly claimed by Spanish. Then I started to learn Hebrew, and that began crowding out the French.

Now, when I speak with my husband’s cousin in Paris, Hebrew words will float to the top first, almost popping out of my mouth before I rein them in, realizing they are not the right language. I have to dig deeper to unearth the French.

Learning another language has always felt like playing catch, struggling to grasp the words and phrases floating around in my gray matter when I am trying to express myself.

I have to catch each word, each phrase, and arrange them on my tongue before they fly out, hopefully in an intelligible way. The more proficient I get, the less conscious this effort becomes. Finally, hopefully, I reach a level of mindless fluency, when I can utter something in French, or Hebrew, without prior mental arrangement.

The springboard for each of my foreign languages have been my native languages, English and German. I learned French in Germany; thus the home base for French was German. After high school I spent a summer in Paris, where my French became fluent. When I later took French classes at the Alliance Française in Chicago, the upkeep of French in an English-speaking environment didn’t require much effort.

Almost ten years ago, I began, in earnest, to learn Hebrew. This time the language of reference was English. However, knowing German helped. The concept of nouns having genders, alien to English, was familiar to me from German (and French). There are other concepts in Hebrew that exist in German, but not in English: For example, both have a different verb for knowing a person versus knowing a thing.

While French and Hebrew now jostle each other in the foreign language compartment, as my foreign languages they have languages of reference. English and German do not. I did not learn them in terms of each other. Instead, they developed independently in the part of my brain that speaks, listens, writes and reads. At least this is how I understand my bilingual life began. When a child learns to speak, it is not a conscious process after all.

In my self awareness, English and German were always present.

I remember distinctly that, during my childhood in Germany, when I spent a week in the hospital as an eight-year-old (for severe stomach pains that probably were undiagnosed celiac disease), I helped my roommate with her 5th grade English homework. How did I know how to read and write in English as a 2nd grader, when English wasn’t taught until 5th grade? My American mother didn’t have an answer when I asked her about that many years later, when my own kids struggled to learn how to read English in the US.

Neither my mom nor my dad taught me how to read in English, nor had anyone else. They did read English-language books to my siblings and me, and their language as a couple was certainly English in the early years of their marriage even though they moved to Germany before their first anniversary. My parents met when my German dad was a PhD student at Purdue University, where my mom worked as a secretary.

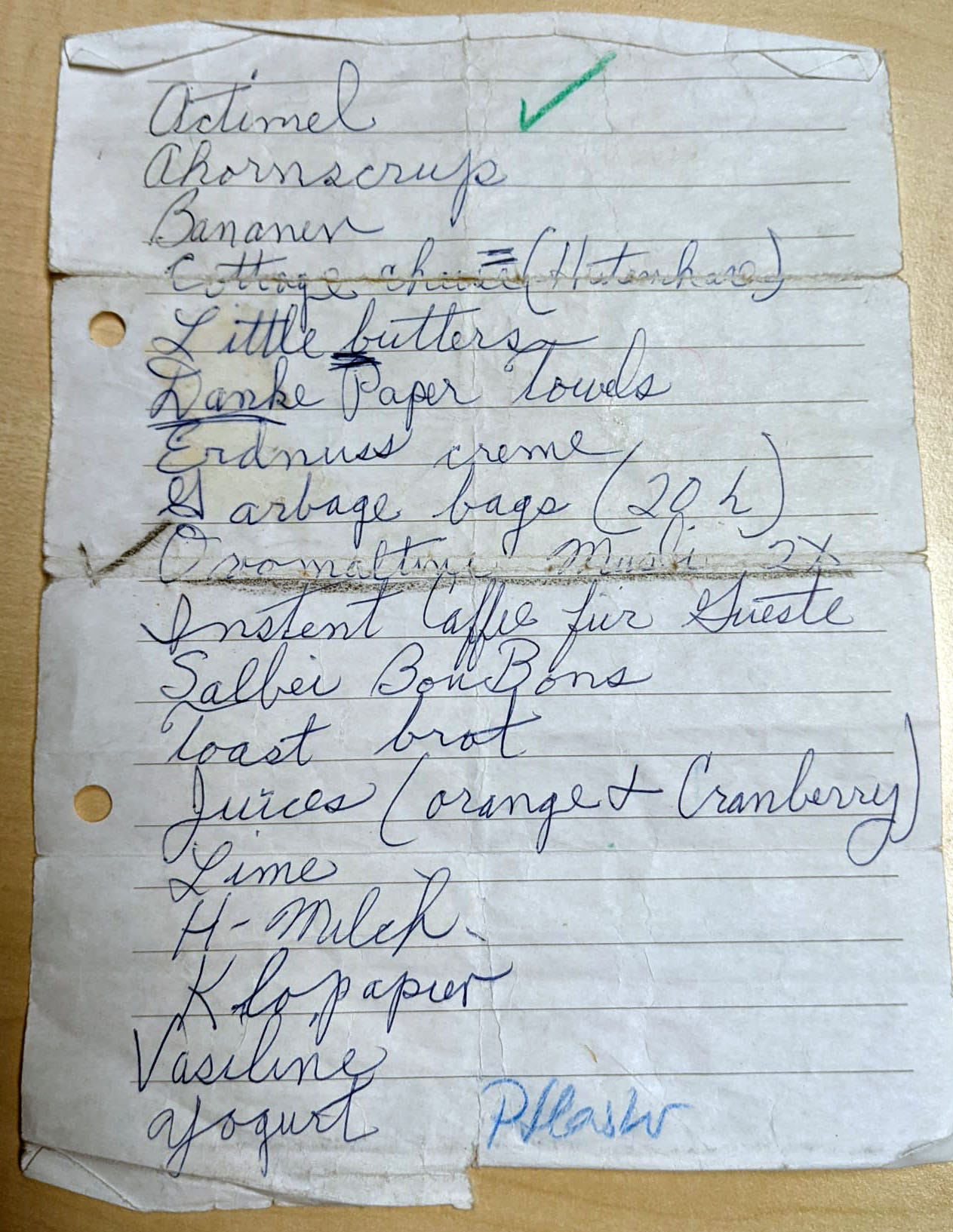

Both English and German have been so much part of my life that I am incapable, for example, of writing a shopping list in one language only.

So was my mom, who lived in Germany from age 27 on. After her recent death, my sister found a crumpled shopping list in Mom’s purse:

“Actimel, Ahornsyrup, Bananen, Cottage cheese, little butters, Danke paper towel, Erdnuss creme, Garbage bags, Ovomaltine Müsli, Instant Coffee für Gäste…”

Like my mom, I jumble English and German in my shopping lists and everyday speech, answering whoever addresses me in the language they used without thinking about it.

If I need to stick to one language because I am aware that the person I am speaking with doesn’t know the other language, I frequently fumble for the right word.

Thus I have never been a good translator from English to German and vice versa.

When I do have to translate something, i.e. find the connection from one language to the other, it feels like I'm shifting gears, and the proper gear isn’t catching on smoothly. When I’m asked, “How do you say that in____?” I'll demur again and again, because I really can’t think of it.

Initially, when I embarked on becoming a writer in the US, and a German word or phrase offered itself instead of an English one as I was drafting a text, I would simply insert it and continue typing. Later, when I tried to find the proper translation, I often came up short. The German word had occurred to me precisely because there was no good English equivalent. Take the word “wuchern” for example, a strong German verb (and you want strong verbs to create vivid prose) that means “to grow profusely.” I had been trying to describe the tree of life growing wildly behind my family’s gravestone, and “wuchern” was indeed the mot juste.

Translating, I discovered, was not the way to develop my voice in English.

It made for bumpy prose. Instead, I had to find some weak English placeholder and move on. As I revised, I would comb over the uneven bits again and again until the right English wording offered itself.

I actually barred myself from reading German literature when I wrote my first book, Jumping Over Shadows. In order to develop my literary voice in English, I needed to live entirely in the English literary world. Reading German literature meant good German prose would bop around in my brain, presenting itself when I was looking for the best way to express something.

I was reminded of this when I found myself translating my own writing.

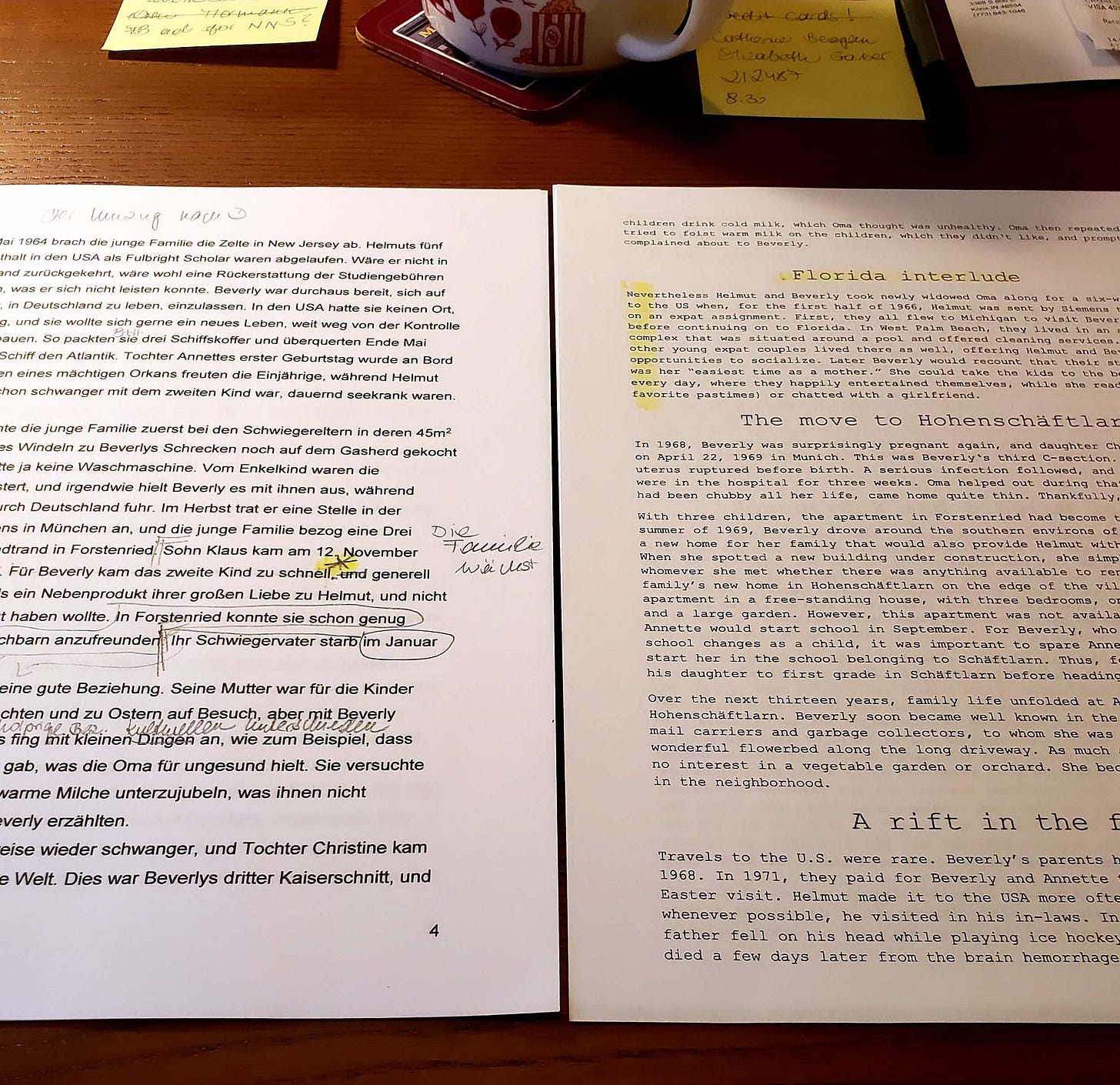

In preparation for my mother’s funeral in Germany last summer, I had written, in German, her life story as background material for the speaker my siblings and I had hired to give the eulogy. Over two hot July evenings, sitting in my sister’s basement, I had banged out thirteen pages about Mom’s life.

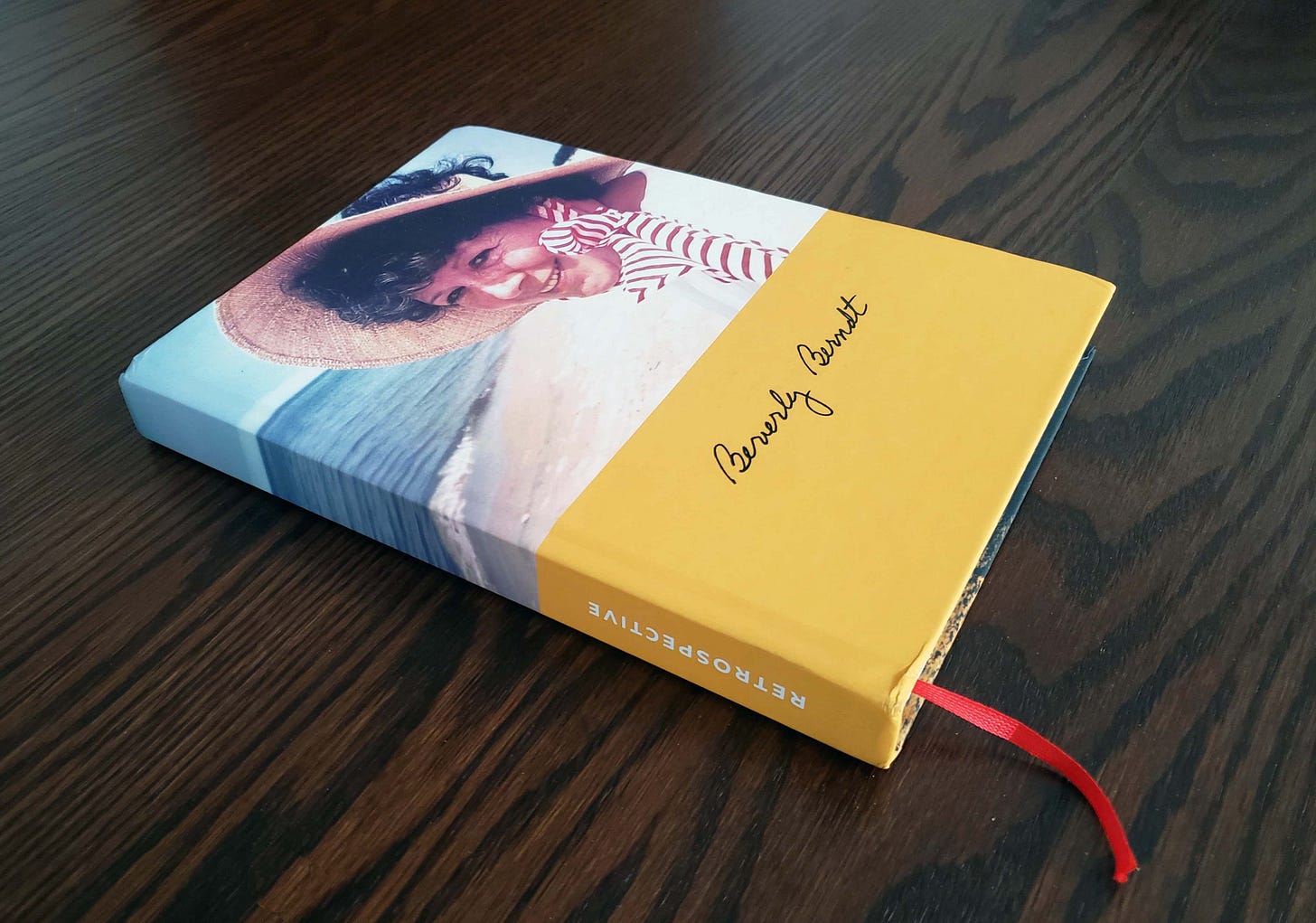

The speaker proved to be fabulous. Among other things, he put together a booklet about Mom as a gift for funeral attendees. It included his eulogy and an array of pictures he’d picked from the cache my brother had sent him. He even prepared an English translation to share with Mom’s relatives in the US.

When my graphic designer brother later spruced up the English version, the booklet morphed into a big photo book. In order to honor Mom’s 86 years of life, he culled photos from our family’s archives. This book was to also include the life story I had written, which necessitated creating an English version.

“Just run it through Google Translate,” my brother advised.

I had an inkling that it wouldn’t be that easy. To my surprise, the English version Google Translate spit out was about 90% accurate. Once I’d gone through all thirteen pages and changed, for example, British terms such as “minced meat” to “ground beef,” I read through the English version again, expecting this to be my final proofread.

I realized, however, that this text, while listing me as the writer and correctly conveying the content, did not sound like I had written it.

Thankfully, my voice as a writer in English is familiar to me, even though I could hardly pinpoint what characterizes it. Does replacing “cut” with “clipped” constitute my voice? Or is “clipped” simply better prose because it conjures an image?

I had to go through the life story several more times. Each time I would iron out another phrase that I realized I would not have used and replace it with my wording, which often only occurred to me on the umpteenth go-around. Still, revising in English was a well-worn path.

In contrast, I found myself in unfamiliar territory when my brother and I embarked upon creating a German version of what we came to call “Mom’s Book.” It was to also feature an essay about Mom’s typical sayings I had drafted, in English, many years earlier and that I had shared with the funeral speaker to give him an idea of Mom as a person.

How would I create a German version of this essay?

Again, Google Translate yielded a text that was about 90% accurate. Again, it did not sound like me at all.

But how did I sound as a writer in German?

I had never worked on creating German prose. Attempting that took many more go-arounds, combing through the AI-generated translation, stumbling over wording that was correct but not “me,” and asking myself, again and again, “How would I put this in German?” I wouldn’t call myself a writer in German just yet, but I did finally arrive at a German version of the essay I was happy with. It sounded like me.

Translating my own writing let me experience that translation involves a lot more than finding the mot juste. The choice of words and syntax have to accurately express the writer’s thoughts and feelings, and convey the content, but they also have to capture the writer’s voice.

Annette, you are amazing and very talented!

I personally related to what you wrote about looking for the right words in another language. In the 49 years that I've lived in Israel I find myself combining expressions which my adult kids find hilarious and my daughter has made lists and even a list of words that American Israeli friends have created!

An example is: we are shiputzing our house! This means we are remodeling! There are lots more!!

Thank you for your insights about finding your own voice while translating. And thank you as well for the wonderful boost you are giving me as I try to write family

stories. Your book " How to write compelling stories from family history" has inspired me to finally start on that journey. You have created a guide that walks beside me, encourages me and offers me such practical tips! Your voice is quiet and almost matter-of-fact, yet it reaches into my soul and brings out the best . Thank you !!